-

Archives

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- March 2015

- January 2015

-

Meta

President Putin … Nordstream 2 – some advice to EU

Vladimir Putin

Posted in Uncategorized

Leave a comment

U.S. & EU DRAW RED LINES FOR IRAN – No more uranium enrichment, – Cut down your missile stash, – Drop support for Hamas, Hezbollah, Houthis, all of it. These are the 3 demands on the table if Iran wants to avoid a potential military response. The ball is in Tehran’s court now. Source:

Posted in Uncategorized

Leave a comment

Highly recommend people engage with Neuralink (Elon Musk). Changes beyond comprehension. Explore Blindsight

and more =========================

Posted in Uncategorized

Leave a comment

Futurism: Google AI … what does it know about you?

The Amount Google’s AI Knows About You Will Cause an Uncomfortable Prickling Sensation on Your Scalp

It “feels like Google has been quietly taking notes on my entire life and finally decided to hand me the notebook.”

Published Jan 28, 2026 2:09 PM EST

We all know that tech companies keep tabs on everything about our online habits. But it’s another thing to actually be confronted with just how much data they have on you.

This was the experience of tech journalist Pranav Dixit, who experimented with using Google’s new “Personal Intelligence” feature for Gemini and its search engine’s AI Mode. And boy, did things get personal. The AI was able to dig up everything from his license plate to his parents’ vacation history, sometimes without it being directly requested.

“Personal Intelligence feels like Google has been quietly taking notes on my entire life and finally decided to hand me the notebook,” Dixit wrote in a piece for Business Insider.

Google rolled out Personal Intelligence to subscribers of Google AI Pro and AI Ultra last week. Once you opt in, the AI can scour your Gmail and Google Photos accounts, and a more powerful version released for the Gemini app earlier this month goes even deeper, raking your Search and YouTube history, too. In short, if you’ve ever used Google for anything, it can probably dig it up.

This represents one way Google intends to keep its edge in the AI race. Unlike competitors such as OpenAI, it has decades’ worth of user data on billions of people. It can infer plenty from your Google searches alone, and your Gmail account is probably littered with confirmations and reminders for all kinds of life events, ranging from doctor’s appointments to hotel bookings to online purchases.

If the idea of letting an AI prowl through all this sounds like a privacy nightmare to you, you’re probably not wrong. Google, for its part, maintains that it’s being careful with your personal secrets, with VP Josh Woodward insisting in a recent blog post that it only trains its AI on your prompts and the responses they generate — not stuff like your photos and emails.

“We don’t train our systems to learn your license plate number,” he summarized. “We train them to understand that when you ask for one, we can locate it.”

Whatever the ethics, Dixit’s estimation is that giving the AI access to your data at least makes for a genuinely useful — and “scary-good,” in his phrasing — personal assistant.

When asked to come up with some sightseeing ideas for his parents, Personal Intelligence correctly inferred that they’d already done plenty of hikes on previous trips to the Bay Area, and suggested some museums and gardens instead.

Gemini told Dixit that it had deduced this from “breadcrumbs” including emails, photos of a forest they trekked in, a parking reservation in Gmail, and a Google search for “easy hikes for seniors.” It also figured out his license plate number based on photos stored in his Google library and scanned his emails to correctly report when his car insurance was up for renewal.

Privacy isn’t the only concern that the feature raises. With the data, chatbots can sound more humanlike, giving the impression that they’re intimately familiar with users’ personal lives. This is a dangerous road to go down amid reports of many people falling down delusional mental health spirals as they come to believe the AIs are trustworthy companions; Dixit touches on this when he complains about how’d he’d “pour my soul into ChatGPT and get a smart answer,” only for it to “forget I existed like a genius goldfish.” Experts have focused on ChatGPT’s “memory” as allowing it to seem too lifelike by drawing on what you’ve said in previous conversations.

More on AI: AI Is Causing Cultural Stagnation, Researchers Find

Frank Landymore

Contributing Writer

I’m a tech and science correspondent for Futurism, where I’m particularly interested in astrophysics, the business and ethics of artificial intelligence and automation, and the environment.

Posted in Uncategorized

Tagged ai, artificial-intelligence, chatgpt, digital-marketing, technology

Leave a comment

The Harvard Gazette: Parental firearm injury linked to surge in children’s psychiatric diagnoses

Menu

Search

Parental firearm injury linked to surge in children’s psychiatric diagnoses

Trauma/post-traumatic stress disorder accounts for most of the increase, according to study

Mass General Brigham Communications

January 28, 2026 3 min read

Each year, 20,000 children and adolescents across the U.S. lose a parent to gun violence, while an estimated two to three times more have a parent who has been injured due to a firearm.

Investigators from Harvard and Mass General Brigham analyzed records from a large health insurance database and found that in the year following a parent’s injury, children had increases in psychiatric diagnoses and mental health visits, especially if the parent had suffered a severe injury.

“Our study draws attention to the way that firearm injuries reverberate through whole families, harming even those who were not injured directly.”George Karandinos

The findings are published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Firearm injury is the most common cause of death in children and adolescents, but as horrific as this fact is, it represents only one way in which gun violence impacts young people,” said lead author George Karandinos, a research investigator in the Gun Violence Prevention Center of Massachusetts General Hospital, and an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School. “As a physician and anthropologist who has worked in areas with concentrated gun violence, I have seen directly how individuals and communities are affected at many levels. By zooming out and using population data, our study draws attention to the way that firearm injuries reverberate through whole families, harming even those who were not injured directly.”

For this study, researchers matched the records of children who had a parent who experienced a firearm injury with records of up to five control children of the same sex, geographic region, and insurance coverage and ensured that the two groups were also closely balanced overall in terms of children’s age and health risks. In total, 3,790 youth exposed to parental firearm injury and 18,535 controls were included, with an average age of 10.7 years.

The researchers found a sharp and persistent increase in rates of psychiatric diagnoses and mental health visits following parental firearm injury in the exposed group alone. Relative to the control group, exposed youth experienced a 42 percent increase in psychiatric diagnoses and 60 percent increase in mental health visits in the year after parental firearm injury.

Mental health impacts of parental firearm injury were especially pronounced in female children and adolescents and for children with a parent whose injuries necessitated intensive-care unit treatment. Trauma/post-traumatic stress disorder diagnoses accounted for most of the increase, but mood disorders, including depression, also increased.

The researchers explained that though their work may underestimate the true mental health impact of firearm violence because it only accounts for formal diagnoses and medical visits, it can nonetheless encourage broader recognition of the need for early, targeted interventions. Hospital-based violence intervention programs and improved communication with pediatricians caring for the children of firearm-injured parents are two options for improving access to mental health care for affected children.

“The mental health need that we have documented in this work is something that can be addressed by leveraging existing programs, while also improving interdisciplinary care coordination after firearm injury,” Karandinos said. “These interventions are intuitive, but funding and supporting them is essential to truly caring for the entire family.”

This research was funded by the National Institute for Health Care Management and the MGH Gun Violence Prevention Center.

Share this article

The Deep View: “AI Humaniser”

| Students use “AI Humanizer” tools to make AI text look human |

| There are telltale signs that AI wrote text, such as em dashes, unnatural sounding sentences, monotonous tone and feigned excitement. But what if AI could help make text sound human? |

| That technology exists: College students are already using AI “humanizers,” according to an NBC News report. As the name implies, these humanizers review text for traces of AI use and then suggest changes to make it look more human written. |

| A quick search for “AI Humanizer” online results in endless options, including some from established companies such as Grammarly, which advertises itself as “a tool that rewrites AI-generated text—like content from Grammarly, ChatGPT, or Claude—to improve clarity, flow and readability.” Quillbot offers a similar AI Humanizer tool that can be added to Chrome for easier access. Both experiences are free, with many paid tools also available. |

| Though students turn to these AI humanizers to hide the fact that they were using AI in the first place, many also use it to protect themselves against wrongful accusations of AI use, NBC news reported. |

| As generative AI tools became more popular, educators were met with the challenge of determining what content was student or AI generated. As a result, they turned to AI plagiarism detectors, which are notorious for incorrectly identifying whether AI was used or not and have falsely accused many students of using AI. Studies have even found that these detectors are biased against non-native English writers. |

| Both educators and students in the report shared frustration with students having to prove that their work is authentic. Even if these students have never touched AI tools, they are being wrongly accused, even in some instances, for handing in high quality work. |

| Ultimately, the rise of AI humanizers are only a symptom to a larger problem: A cat and mouse chase in which, as AI systems become more advanced, so does paranoia about AI-generated content, discouraging students from bothering to produce good work at all. |

| A more permanent solution that goes beyond AI humanizers and detectors requires educators to shift assignments and testing to reflect the AI-first era we live in, such as moving more towards in-class assignments or testing for comprehension rather than execution. |

|

| The demand for AI humanizers highlights a continued reliance on AI tools. Even in instances where using AI tools could cause negative consequences for the user, instead of pivoting away from using it or learning to use it more collaboratively, such as for outlining essays, people are instead looking for tools that help them get away with having AI do the work. This is where AI literacy could help, as ultimately, people need to understand the negative impacts go beyond getting caught, but could cause the retrogression to their own skill developments. |

Posted in Uncategorized

Tagged ai, artificial-intelligence, chatgpt, education, writing

Leave a comment

GZERO: Hard Numbers: Cuba’s oil reserves running try. China executes alleged Myanmar scammers…..

15-20: The number of days before Cuba’s oil reserves run dry, according to the data firm Kpler, should it continue at current levels of demand and domestic production. This comes as Mexico, the largest supplier of crude to Cuba, has halted some oil exports to the island. Cuba’s economy is already deteriorating, but with Venezuela’s oil supplies now shut off, it may get even worse.

Posted in Uncategorized

Leave a comment

Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists: Quote: “Because of this failure of leadership, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists Science and Security Board today sets the Doomsday Clock at 85 seconds to midnight, the closest it has ever been to catastrophe.” Comment: Be Aware how dangerously close we are to midnight

It is now 85 seconds to midnight

2026 Doomsday Clock Statement

Science and Security Board

Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

Editor, John Mecklin

January 27, 2026

Founded in 1945 by Albert Einstein, J. Robert Oppenheimer, and University of Chicago scientists who helped develop the first atomic weapons in the Manhattan Project, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists created the Doomsday Clock two years later, using the imagery of apocalypse (midnight) and the contemporary idiom of nuclear explosion (countdown to zero) to convey threats to humanity and the planet. The Doomsday Clock is set every year by the Bulletin’s Science and Security Board in consultation with its Board of Sponsors, which includes eight Nobel laureates. The Clock has become a universally recognized indicator of the world’s vulnerability to global catastrophe caused by man-made technologies.

The Science and Security Board

The Bulletin‘s Science and Security Board (SASB) is composed of a select group of globally recognized leaders with a specific focus on nuclear risk, climate change, and disruptive technologies. Learn more…

It is now 85 seconds to midnight

A year ago, we warned that the world was perilously close to global disaster and that any delay in reversing course increased the probability of catastrophe. Rather than heed this warning, Russia, China, the United States, and other major countries have instead become increasingly aggressive, adversarial, and nationalistic. Hard-won global understandings are collapsing, accelerating a winner-takes-all great power competition and undermining the international cooperation critical to reducing the risks of nuclear war, climate change, the misuse of biotechnology, the potential threat of artificial intelligence, and other apocalyptic dangers. Far too many leaders have grown complacent and indifferent, in many cases adopting rhetoric and policies that accelerate rather than mitigate these existential risks. Because of this failure of leadership, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists Science and Security Board today sets the Doomsday Clock at 85 seconds to midnight, the closest it has ever been to catastrophe.

Last year started with a glimmer of hope in regard to nuclear risks, as incoming US President Donald Trump made efforts to halt the Russia-Ukraine war and even suggested that major powers pursue “denuclearization.” Over the course of 2025, however, negative trends—old and new—intensified, with three regional conflicts involving nuclear powers all threatening to escalate. The Russia–Ukraine war has featured novel and potentially destabilizing military tactics and Russian allusions to nuclear weapons use. Conflict between India and Pakistan erupted in May, leading to cross-border drone and missile attacks amid nuclear brinkmanship. In June, Israel and the United States launched aerial attacks on Iranian nuclear facilities suspected of supporting the country’s nuclear weapons ambitions. It remains unclear whether the attacks constrained those efforts—or if they instead persuaded the country to pursue nuclear weapons covertly.

Meanwhile, competition among major powers has become a full-blown arms race, as evidenced by increasing numbers of nuclear warheads and platforms in China, and the modernization of nuclear delivery systems in the United States, Russia, and China. The United States plans to deploy a new, multilayered missile defense system, Golden Dome, that will include space-based interceptors, increasing the probability of conflict in space and likely fueling a new space-based arms race. As these worrying trends continued, countries with nuclear weapons failed to talk about strategic stability or arms control, much less nuclear disarmament, and questions about US extended deterrence commitments to traditional allies in Europe and Asia led some countries without nuclear weapons to consider acquiring them. As we publish this statement, the last major agreement limiting the numbers of strategic nuclear weapons deployed by the United States and Russia, New START, is set to expire, ending nearly 60 years of efforts to constrain nuclear competition between the world’s two largest nuclear countries. In addition, the US administration may be considering the resumption of explosive nuclear testing, further accelerating a renewed nuclear arms race.

An array of adverse trends also dominated the climate change outlook in the past year. The level of atmospheric carbon dioxide—the greenhouse gas most responsible for human-caused climate change—reached a new high, rising to 150 percent of preindustrial levels. Global average temperature in 2024 was the warmest in the 175-year record, and temperatures in 2025 were similar. With the addition of freshwater from melting glaciers and thermal expansion, global average sea level reached a record high. Energized by warm temperatures, the hydrologic cycle became more erratic, with deluges and droughts hopscotching around the globe. Large swaths of Peru, the Amazon, southern Africa, and northwest Africa experienced droughts. For the third time in the last four years Europe experienced more than 60,000 heat-related deaths. Floods in the Congo River Basin displaced 350,000 people, and record rainfall in southeast Brazil displaced over half a million.

The national and international responses to the climate emergency went from wholly insufficient to profoundly destructive. None of the three most recent UN climate summits emphasized phasing out fossil fuels or monitoring carbon dioxide emissions. In the United States, the Trump administration has essentially declared war on renewable energy and sensible climate policies, relentlessly gutting national efforts to combat climate change.

During the past year, developments in four areas of the life sciences have increased potentially catastrophic risks. In December 2024, scientists from nine countries announced the recognition of a potentially existential threat to all life on Earth: the laboratory synthesis of so-called “mirror life.” Those scientists urged that mirror bacteria and other mirror cells—composed of chemically-synthesized molecules that are mirror-images of those found on Earth, much as a left hand mirrors a right hand—not be created, because a self-replicating mirror cell could plausibly evade normal controls on growth, spread throughout all ecosystems, and eventually cause the widespread death of humans, other animals, and plants, potentially disrupting all life on Earth. So far, however, the international community has not arrived at a plan to address this risk.

At the same time, the accelerating evolution of artificial intelligence poses a different sort of biological threat: the potential for the AI-aided design of new pathogens to which humans have no effective defenses. Also, concerns about state-sponsored biological weapons programs have deepened due to the weakening during this past year of international norms and mechanisms for productive engagement. Perhaps of most immediate concern is the rapid degradation of US public health infrastructure and expertise. This dangerously reduces the ability of the United States and other nations to respond to pandemics and other biological threats.

The increasing sophistication of large language models and their applications in critical processes—coupled with lingering concerns about their accuracy and tendency to “hallucinate”—have generated significant public debate over the past year about the potential risks of artificial intelligence. The United States, Russia and China are incorporating AI across their defense sectors, despite the potential dangers of such moves. In the United States, the Trump administration has revoked a previous executive order on AI safety, reflecting a dangerous prioritization of innovation over safety. And the AI revolution has the potential to accelerate the existing chaos and dysfunction in the world’s information ecosystem, supercharging mis- and disinformation campaigns and undermining the fact-based public discussions required to address urgent major threats like nuclear war, pandemics, and climate change.

These dangerous trends are accompanied by another development that undermines efforts to deal with major global threats: the rise of nationalistic autocracy in countries around the world, including in a number of countries that possess nuclear weapons. Leaders of the United States, Russia, and China greatly vary in their autocratic leanings, but they all have approaches to international relations that favor grandiosity and competition over diplomacy and cooperation. The rise of autocracies is not in itself an existential threat, but an us-versus-them, zero-sum approach increases the risk of global catastrophe. The current autocratic trend impedes international cooperation, reduces accountability, and acts as a threat accelerant, making dangerous nuclear, climatic, and technological threats all the harder to reverse.

Even as the hands of the Doomsday Clock move closer to midnight, there are many actions that could pull humanity back from the brink:

- The United States and Russia can resume dialogue about limiting their nuclear arsenals. All nuclear-armed states can avoid destabilizing investments in missile defense and observe the existing moratorium on explosive nuclear testing.

- Through both multilateral agreements and national regulations, the international community can take all feasible steps to prevent the creation of mirror life and cooperate on meaningful measures to reduce the prospect that AI be used to create biological threats.

- The United States Congress can repudiate President Trump’s war on renewable energy, instead providing incentives and investments that will enable rapid reduction in fossil fuel use.

- The United States, Russia, and China can engage in bilateral and multilateral dialogue on meaningful guidelines regarding the incorporation of artificial intelligence in their militaries, particularly in nuclear command and control systems.

Our current trajectory is unsustainable. National leaders—particularly those in the United States, Russia, and China—must take the lead in finding a path away from the brink. Citizens must insist they do so.

It is 85 seconds to midnight.

Editor’s note: Additional information on the threats posed by nuclear weapons, climate change, biological events, and the misuse of other disruptive technologies can be found elsewhere on this page and in the full PDF / print version of the Doomsday Clock statement.

Learn more about how each of the Bulletin‘s areas of concern contributed to the setting of the Doomsday Clock this year:

Nuclear Risk

The lack of arms control talks and a general dearth of leadership on nuclear issues has worsened the nuclear outlook. Read more…

Climate Change

Reducing the threat of climate catastrophe requires actions both to reduce the primary cause—the burning of fossil fuels—and to deal with the damage climate change is already causing. Read more…

Biological Threats

Four developments—research into self-replicating “mirror life”; AI tools that can design biological threats; state-sponsored biological weapons programs; and the dismantling of US public health efforts—have increased the possibility of bio-catastrophe. Read more…

Disruptive Technologies

The increasing sophistication and uncertain accuracy of AI models have generated significant concern about their application in critical processes, particularly in military programs. Read more…

About the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

At our core, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists is a media organization, publishing a free-access website and a bimonthly magazine. But we are much more. The Bulletin’s website, iconic Doomsday Clock, and regular events equip the public, policy makers, and scientists with the information needed to reduce man-made threats to our existence. The Bulletin focuses on three main areas: nuclear risk, climate change, and disruptive technologies, including developments in biotechnology. What connects these topics is a driving belief that because humans created them, we can control them.

The Bulletin is an independent, nonprofit 501(c)(3) organization. We gather the most informed and influential voices tracking man-made threats and bring their innovative thinking to a global audience. We apply intellectual rigor to the conversation and do not shrink from alarming truths.

The Bulletin has many audiences: the general public, which will ultimately benefit or suffer from scientific breakthroughs; policy makers, whose duty is to harness those breakthroughs for good; and the scientists themselves, who produce those technological advances and thus bear a special responsibility. Our community is international, with more than half of our website visitors coming from outside the United States. It is also young. Half are under the age of 35.

Learn more at thebulletin.org/about-us.

The MIT Press Reader: The same technology that’s ruining essay writing as a pedagogical tool can help students learn how to reason via conversations. Comment: Imagine the impact of this for people who have TBI or stroke …

AI Can Teach Our Students the Art of Dialogue

The same technology that’s ruining essay writing as a pedagogical tool can help students learn how to reason via conversations.

By: David Weinberger

Recent research from MIT found that students using AI to help them structure and outline essays showed less executive brain activity than unaided students. Even more troubling, the effect carried over to when they later wrote an essay on their own. That’s quite concerning, of course.

But instead of taking this as proof that AI fatally weakens our intellectual capabilities, we might also see it as an opportunity to reclaim a powerful and needful skill: helping students learn to think through thoughtful, open dialogue. After all, most students are rarely going to write essays and reports after they graduate. But we hope they will all be able to engage in constructive conversations that broaden and deepen their thinking.

AI can be a powerful, even game-changing tool in this pursuit. As many of us have learned, the large language models such as ChatGPT, Gemini, and Claude are not simply vending machines for answers. You can “talk” with them, drill down on a topic, challenge them, or expand a “conversation” in unexpected directions.

As a small example, here’s the beginning of a conversation I had with Claude, based on my prompt asking it to assume I’m a college freshman and to challenge my ideas. At the end, I had Claude compress it for this brief article:

STUDENT: We did the Ship of Theseus in class today. You replace all the planks, and then everyone argues about whether it’s the same ship. I honestly don’t see why that’s supposed to be a big deal. It just depends on how you’re using the word “same.”

LLM: That’s reasonable — maybe it is just semantic. Though, are you the same person you were when you were five? Your cells have mostly been replaced.

STUDENT: I’m the same person in a different body.

LLM: So, what stays the same — the person part? Your memories and personality have changed pretty dramatically, too.

STUDENT: Yeah, but they’re not planks you swap out, like with the ship. My new memories build on my old ones.

LLM: Oh, that’s good. So, it’s about developmental continuity, not just continuity? That makes me reconsider the ship — planks don’t grow together. But what about a river? New water constantly flows through, yet it’s the same river.

STUDENT: The river’s defined by its shape, not its water.

LLM: Right — so for rivers it’s structure, for persons it’s developmental continuity. What about nations? Is America the same country as it was in 1800?

STUDENT: Probably developmental continuity, but that’s my point: Sameness is just definitional. Who cares?

LLM: But you rejected some definitions as wrong. Maybe we’re not choosing randomly — maybe what we mean by sameness tracks with what actually matters? Like, it matters whether someone who committed a crime decades ago is “the same person” we punish today.

This is not an AI writing an essay for the student. It’s a quick example of a student thinking through an idea in conversation — probing, being challenged, defending their point of view, and perhaps heading toward a reevaluation of their argument. Engaging this way is a fundamentally intellectual activity, hard to teach because it requires the one-on-one attention that few teachers can afford under today’s stresses. But AI can offer students individualized attention at scale, helping them become critical and constructive thinkers by engaging them in respectful, probing dialogues that aim to discover and test ideas, as we did in the ancient roots of Western thought.

When I was a philosophy graduate student, we got one full hour of teacher training. Despite the session’s ludicrous brevity, one line has stuck with me for many decades: Don’t teach the course you would have wanted as an undergraduate. (Thank you, Professor Frank Cunningham.) In other words, we in the room were the one percent who went on to study philosophy as graduate students, and as teachers, we needed to serve the needs and interests of the 99 percent who would not.

Similarly, writing essays won’t be a part of most students’ work once they graduate. This isn’t to say that students shouldn’t write any essays while in school. After all, writing essays also teaches students how to read them: how to follow an argument’s flow, listen with sympathy, evaluate evidence, and challenge ideas. Clearly, those skills are crucial for learning how to think, but they are not the only skills needed for post-collegiate success. Real-time conversations require listening, finding points of common interest, flexing and diverging as appropriate, and following a complex set of social rules for respectful interaction. (Rupert Wegerif has written brilliantly about this as a pedagogy.)

AI enables us to pursue an idea from history to physics to literature to pop culture to feminist ethics, and beyond, all in one sitting.

In fact, this is precisely why Socrates was so skeptical of the written word: In the “Phaedrus,” he lists three drawbacks of writing: It weakens our memory; it gives the same fixed text to everyone rather than adapting to the individual reader; and you can’t ask a written document a question. You don’t have to deny the importance of literacy to see the merit of his critiques: Certainly, outsourcing memory to documents has diminished our memory. (Remember when the local bards recited thousands of lines from “The Iliad” as we listened, enthralled? Me neither.)

But learning to converse about ideas with AI can overcome Socrates’ second and third criticisms. First, we’re on the verge of language models responding in ways closely tailored to the particularities of each learner’s interests, knowledge level, and conversational style. Second, unlike a static text, you can ask questions of an LLM, and it will answer, often uncannily well (and sometimes wildly incorrectly, which students must be taught how to detect).

There’s also been an epochal change since Socrates’ time. He believed the reasoning exercised in a good conversation could be applied to any topic; that’s an implication of his claim that he knew nothing yet could engage in worthwhile conversations with generals about courage, politicians about virtue, religious experts about piety, and so on. Today, topical knowledge matters more than ever, which can lead to the fragmentation of understanding into separate fields, each requiring deep expertise. But AI enables us to pursue an idea from history to physics to literature to pop culture to feminist ethics, and beyond, all in one sitting. That sort of freedom unleashes curiosity, which is itself a pedagogical good. So is letting students experience the interconnectedness of all knowledge — a reflection of the world’s own callous disregard of disciplinary boundaries.

None of this means AI is a substitute for human teachers or that its answers should be trusted uncritically. On the contrary, AI’s errors and biases make it useful for teaching critical skills: Students must learn how to push back, question sources, and test claims. And teaching them to do this in a conversation with no social stakes can make students more fearless in their critiques.

In human-to-human dialogues, there are stakes — for one thing, developing social and community bonds — so AI dialogues should not be presented as a replacement for human-to-human conversations or human mentorship. This should be clearly demonstrated in the class itself.

The teacher remains essential to this project. When students turn in transcripts of an AI conversation instead of an essay, the teacher would grade it, commenting on the dialogue’s flow and process, as well as its substance. What did the student probe and why? Where were they too trusting? What assumptions went unchallenged? What seems dubious in what the AI asserts so confidently? The teacher can also lead classroom discussions of the process by which we can discover and test ideas conversationally.

AI’s errors and biases make it useful for teaching critical skills: Students must learn how to push back, question sources, and test claims.

Crucially, students should be allowed to discuss one another’s AI dialogues, identify their strengths and weaknesses, and continue the collaborative thought process in fully human spaces. This would turn the exercise into an occasion for human-to-human interaction, which is ultimately its aim.

Used this way, AI is not a plagiarism machine but a tool for developing ideas by learning to explore them in conversation. At a moment when thoughtful dialogue too often gives way to dismissal or disdain, learning to develop and critique ideas via conversation is a crucial skill to cultivate. Now more than ever.

David Weinberger, PhD, is an author, philosopher, and researcher at Harvard’s metaLAB, with a 20-year affiliation with Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center. He is the editor of MIT Press’s open-access book series, “Strong Ideas,” and has published widely in articles and multiple books. His forthcoming book, “Beautiful Particulars,” will be published in October by MIT Press.

Posted on Jan 20

Posted in Uncategorized

Tagged ai, artificial-intelligence, education, teaching, writing

Leave a comment

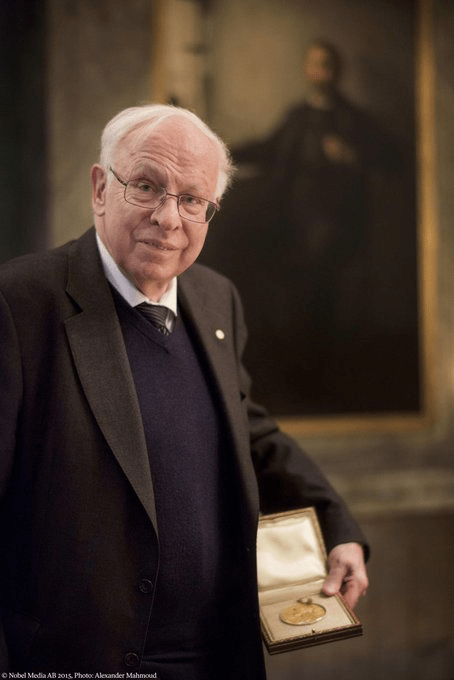

The Nobel Prize: Clash of characters between teachers and students. Never let a teacher destroy your confidence.

“I had a teacher that didn’t like me and I didn’t like him. At the end of the year he decided to fail me. The ironic thing is that the topic was chemistry. I have the distinction of being the only chemistry laureate who failed the topic in high school!” – Tomas Lindahl

Posted in Uncategorized

Leave a comment

“There is one pipe left of Nord Stream 2, it’s not damaged and can deliver 27.5 trillion cubic meters of gas. It only takes a decision from the German government today and tomorrow we turn on the tap, but they aren’t making it because Washington says no.” Europe’s geniuses have now completely banned cheaper Russian gas so they can import more expensive LNG from the US, the country profiting from their deindustrialisation and the country that is actively seeking to annex the territory of a NATO country. A masterclass in economics and geopolitics by Europe!

“There is one pipe left of Nord Stream 2, it’s not damaged and can deliver 27.5 trillion cubic meters of gas. It only takes a decision from the German government today and tomorrow we turn on the tap, but they aren’t making it because Washington says no.” Europe’s geniuses have now completely banned cheaper Russian gas so they can import more expensive LNG from the US, the country profiting from their deindustrialisation and the country that is actively seeking to annex the territory of a NATO country. A masterclass in economics and geopolitics by Europe!