AI Is Forcing Employees to Work Harder Than Ever

Even if AI does increase productivity, it’s not exactly good news for workers.

Published Mar 12, 2026 8:57 AM EDT

Sign up to see the future, today

Can’t-miss innovations from the bleeding edge of science and tech Email address Sign Up

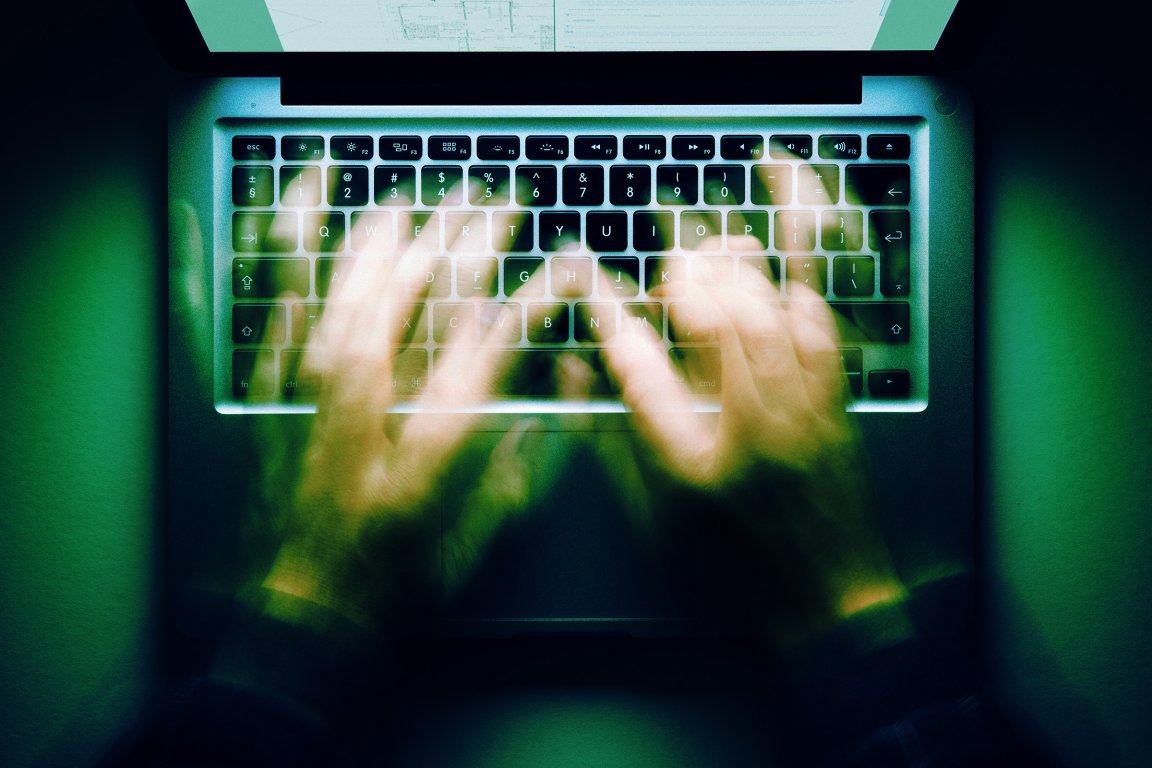

More and more research shows that introducing AI in the workplace is actually forcing employees to work harder, instead of making their jobs easier.

The latest comes from a new analysis from ActivTrak of over 164,000 workers’ digital work activity. After examining their activity 180 days before and after the employees started using AI at work, the software company found that AI “intensified” their jobs in nearly every category, the Wall Street Journal reported. The time they spent on email, messaging, and chat apps more than doubled, while their use of business software surged by 94 percent.

Strikingly, this came at the expense of the time workers spent on highly focused, uninterrupted work, which fell by 9 percent for AI users, and stayed the same for AI abstainers. The study suggests that there may be a “sweet spot” of AI usage, citing the finding that workers who spent 7 to 10 percent of their total work hours using AI showed the highest productivity, but only three percent of AI users fell in this range.

“It’s not that AI doesn’t create efficiency,” Gabriela Mauch, ActivTrak’s chief customer officer and head of its productivity lab, told the WSJ. “It’s that the capacity it frees up immediately gets repurposed into doing other work, and that’s where the creep is likely to happen.”

The findings, which the WSJ reports is one of the biggest studies on AI’s effects on work habits so far, come fresh off a study published by Harvard Business Review that also concluded AI was intensifying work instead of reducing workloads. In the ongoing study, which focused on employees at a tech firm where AI usage was voluntary, the researchers found that AI caused a “workload creep,” in which the employees unknowingly took on more tasks than was sustainable for them to keep up. In this vicious cycle, AI raised expectations on the speed that workers had to perform, which in turn made them more reliant on AI to keep up with the greater demands.

In short, the time that workers might be saving by using AI isn’t being passed on to the workers. It only raises their own expectations, or their bosses’ expectations, of how much work they should do — which has them going straight back into AI tools; the ActivTrak data showed that the average time workers spent using them has risen eightfold from two years ago, per the WSJ, with AI adoption rising to 80 percent.

“Workers often use the time savings to do more work rather than less because AI makes additional tasks feel easy and accessible, creating a sense of momentum,” Aruna Ranganathan from UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Businesses, who led the ongoing study on AI “workload creep,” told the WSJ. Though it may boost productivity in the short-run, over time it “can lead to cognitive overload, burnout, poorer decision-making and declining work quality,” she warned.

Another recent study focused on the draining mental toll that AI causes among workers, coining the troubling phenomenon of “AI brain fry.” It identified information overload and task switching that the tech encourages as some of the main culprits behind it, echoing the testimony of some programmers who’ve been emboldened by recent interest in the topic to criticize how AI is being used at their jobs. But the most mentally fatiguing aspect, the work found, was having to constantly supervise the AI tools, with some employees overseeing multiple AI agents performing different tasks at the same time.

More on AI: Anthropic Announces Jobs Most at Risk From AI

Frank Landymore

Contributing Writer

I’m a tech and science correspondent for Futurism, where I’m particularly interested in astrophysics, the business and ethics of artificial intelligence and automation, and the environment.

The Strait of Hormuz, which carries about 25% of the world’s seaborne oil supply, is 21 nautical miles wide at its narrowest point, and skirts Iran’s southern border. Satellite image: Gallo Images via Getty Images

The Strait of Hormuz, which carries about 25% of the world’s seaborne oil supply, is 21 nautical miles wide at its narrowest point, and skirts Iran’s southern border. Satellite image: Gallo Images via Getty Images

Today’s New York Times, Financial Times headlines

Today’s New York Times, Financial Times headlines