Memorizing London’s 25,000 streets changes cabbies’ brains — and may prevent Alzheimer’s

One of the toughest vocational exams in the world requires candidates to memorize 25,000 streets in an area five times the size of Manhattan.

Jan 27, 2026

This article is an early look at our upcoming special issue on Mastery. Check back tomorrow, January 28th, to catch the full issue.

By Frank Jacobs

To the casual observer, a London taxi driver is just a guy who knows a shortcut to Heathrow and has strong opinions on local weather and politics (“This bloody Starmer and his leftie government”). But to a neuroscientist, that cabbie is a miracle of neuroplasticity.

Why? Because you can’t become a London cabbie without mastering “The Knowledge.” As they cram the chaotic layout of one of the world’s most complex city grids into their heads, aspiring cabbies don’t just learn a map. They physically redesign and grow their brain.

A “brainbuilding” exercise with unexpected side effects

This “brainbuilding” exercise comes with a couple of unexpected side effects, one slightly negative, the other amazingly positive. But first, a bit of history.

Let’s rewind to 1851, when The Knowledge was born out of chaos. That year, the Great Exhibition — a Victorian extravaganza of crystal palaces and curious inventions — drew massive crowds to London, overwhelming the horse-drawn hacks of the day. Cabbies were getting lost, and fares were furious. To prevent further navigational anarchy, authorities created an exam to ensure cabbies actually knew where they were going.

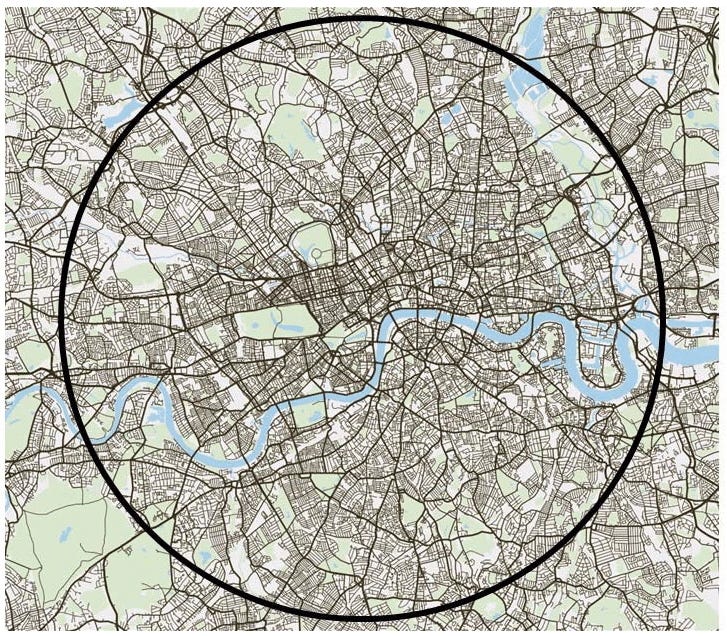

The test that ensued was a beast of a challenge. “The Knowledge of London” is widely regarded as one of the toughest vocational tests in the world. It requires drivers to memorize the labyrinthine web of streets within a six-mile radius of Charing Cross, the traditional midpoint for measuring distances in London.

This is an area of about 113 square miles (293 km2) of urban spaghetti. For comparison, that’s about five times the size of Manhattan — but instead of straight streets and avenues, you have crooked lanes and ways.

The area encompasses about 25,000 streets, which candidates must learn by heart. But that’s just the skeleton. The meaty bit is the 100,000 landmarks they are expected to know and locate: hotels, hospitals, theaters, police stations, courts, clubs, parks, statues, and more.

The Knowledge takes two to four years to master.

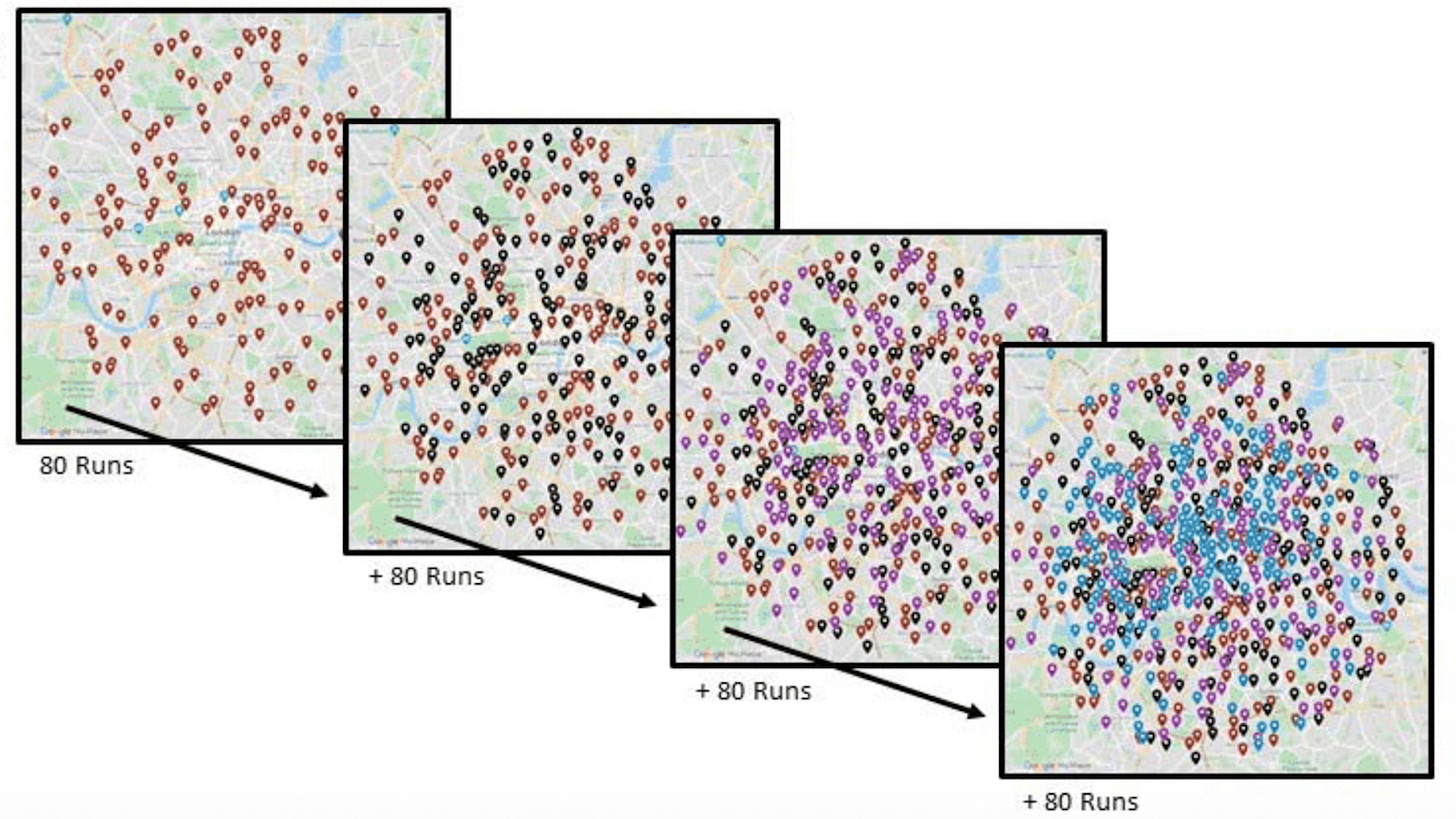

The backbone of The Knowledge is the 320 so-called “runs”: basic routes canonized by Transport for London in the Blue Book, the Bible for would-be cabbies.

Studying The Knowledge is not something you do only in the evenings and weekends. It’s a full-time occupation that entirely takes over your life.

On average, it takes “Knowledge Boys” (the affectionate name for candidates; there is only a smattering of “Knowledge Girls”) two to four years to master The Knowledge. Five years is not an exception, but 18 months — the fastest so far — is. You can see them scootering around the city, clipboard strapped to the handlebars. They spend up to 15 hours a day on the road, literally shouting out the names of streets and landmarks as they drive — a popular memorizing method.

In total, candidates log anywhere between 30,000 and 50,000 miles (about 48,000 to 80,000 km) on the scooter. That’s roughly once or twice around the Earth. Without using GPS — that goes without saying.

Examiners grill candidates in a grueling one-on-one oral test. They are asked to recite several routes (“Manor House Station to Gibson Square”), naming every street, every turn, and every roundabout on their trip. At any point, they can be requested to name the landmarks to their left or right. Or the nearest police station or hospital. Or to reverse on the spot. A slight hesitation is enough to cost them points.

Only 20% to 30% of starters survive the process and earn their green badge. Famous failures include Roger Moore, the suavest James Bond, and Stephen Fry, Britain’s most famous polymath.

A new home for curious minds

Magazines, memberships, and meaning.

Use it or lose it

Today, an army of 24,000 licensed cabbies (only 3% of whom are women) ply the streets of London in the traditional black cabs. Since 2021, they have been allowed to use satnav, but they must still be able to do without. The government protects the profession by allowing only black cabs to be hailed on the street (all other hired car services — minicabs, Uber, and the like — must be pre-booked).

As they learn and practice their profession, London cabbies don’t just fill their brain with knowledge — the knowledge literally changes their brain.

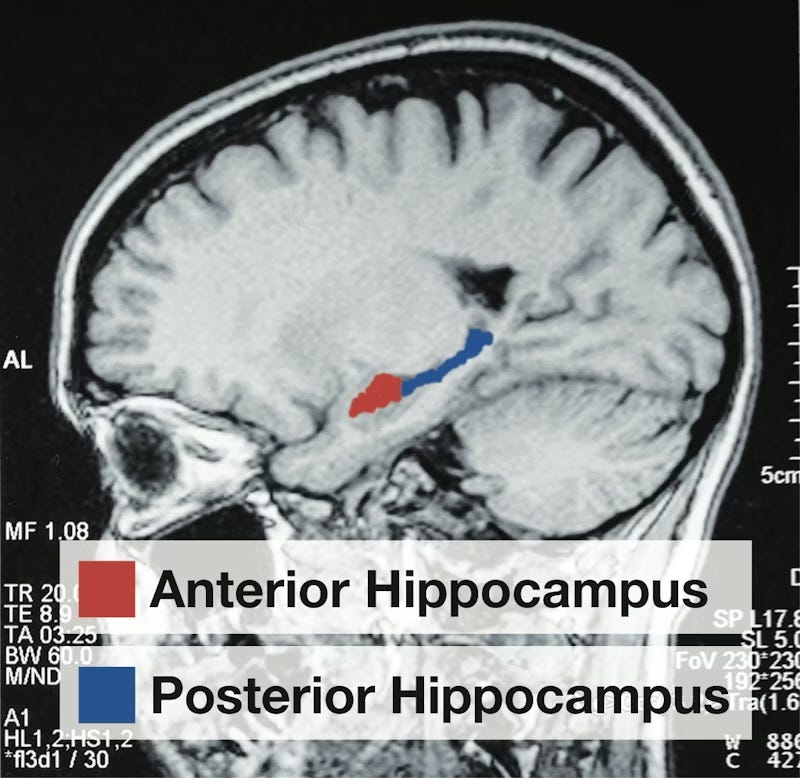

In 2000, the MRI scans that neuroscientist Eleanor Maguire took of London cabbies showed they all had a significantly larger posterior hippocampus — the seahorse-shaped nugget in our brain tied to spatial memory and navigation. The more years of experience a cabbie had, the larger their hippocampus.

Later research clarified that while those who had passed the exams had measurable hippocampal growth, this was not the case for those who failed the test. It was also shown that when cabbies retired, the hippocampus shrank back down — “use it or lose it,” indeed.

This supports the theory that the brain is not so much a bucket to be filled, but a muscle to be trained. The transformation in the hippocampi of London cabbies is so dramatic that they’re regularly cited alongside musicians, bilinguals, and jugglers in textbooks about adult neuroplasticity (i.e., the ability of the adult brain to reshape itself by training).

But cabbies are in a league of their own: Their brains don’t just learn maps — they become maps.

A 2021 study shows how trainee cabbies learn by layering streets like a living GIS system, turning abstract geography into visceral knowledge. This gives them lightning-fast planning abilities, which is why experienced cabbies can navigate more efficiently than “Butter Boys,” the slang term for newly licensed cabbies.

Crossing Vauxhall Bridge on a windy day

Training for The Knowledge is both spatial and embodied. Trainees do not merely read maps — they trace the city with their bodies, building a three-dimensional mental atlas through repeated, multi-sensory immersion. This teaches them what crossing Vauxhall Bridge feels like on a windy day and the angle of the left turn onto Shaftesbury Avenue.

Another study made a useful distinction between taxi drivers and bus drivers. Although both spend long hours behind the wheel, cabbies creatively navigate London’s spaghetti bowl of streets, while bus drivers follow fixed routes. That explains why bus drivers don’t have enlarged hippocampi.

All that work building a mental map of London pays off in more ways than one. The specific area that cabbies bulk up is often the first to atrophy as Alzheimer’s strikes. Recent research suggests that taxi drivers (and ambulance drivers) have some of the lowest mortality rates due to Alzheimer’s. It seems that a lifelong practice of spatial processing builds up a cognitive reserve against the onset of the disease, which is often experienced as spatial disorientation.

There is, however, also one downside to having a pumped posterior (back) hippocampus. Mental real estate being finite, there is bound to be a trade-off, and studies show that it is a slimmer anterior (front) hippocampus. This has negative implications for cabbies’ non-spatial visual memory.

Specifically, cabbies performed below average on the Rey-Osterrieth Figure Test, which requires subjects to draw complex, abstract shapes from memory. In other words, by hyper-specializing their brains to store a massive, detailed map of the city, it seems cabbies sacrificed some ability to process other types of visual information. Not knowingly or willingly. But the brain enforces its own urban planning.

Most cabbies would be willing to pay that small price for their mastery of The Knowledge. In fact, their cognitive maps are so unique that some computer scientists have studied cabbie navigation to improve GPS routing algorithms by mimicking their more intuitive routing practices. Yes, humans may yet teach machines something about how to navigate a city.

The Knowledge is living proof that the brain is a gloriously malleable instrument that can change with our evolving needs even into adulthood. We can train it to contain an entire city, even one as notoriously untamable as London.

The next time you take a black cab in London, marvel at the living atlas behind the wheel. Know that the driver has a posterior hippocampus larger than yours. And that he or she’s earned it, one London street at a time.

Strange Maps #1283

Mini Philosophy | Starts With A Bang | Big Think Books | Big Think Business

Discussion about this post

Fascinating!!!! Thanks