Chasing the Mirage of “Ethical” AI

Isaac Asimov’s “Handbook of Robotics” imagined simple rules for machine morality. But reality is a maze of contradictions, biases, and blind spots.

By: De Kai

Artificial intelligence poses many threats to the world, but the most critical existential danger lies in the convergence of two AI-powered phenomena: hyperpolarization accompanied by hyperweaponization. Alarmingly, AI is accelerating hyperpolarization while simultaneously enabling hyperweaponization by democratizing weapons of mass destruction (WMDs).

For the first time in human history, lethal drones can be constructed with over-the-counter parts. This means anyone can make killer squadrons of AI-based weapons that fit in the palm of a hand. Worse yet, the AI in computational biology has made genetically engineered bioweapons a living room technology.

How do we handle such a polarized era when anyone, in their antagonism or despair, can run down to the homebuilder’s store and buy all they need to assemble a remote-operated or fully autonomous WMD?

It’s not the AI overlords destroying humanity that we need to worry about so much as a hyperpolarized, hyperweaponized humanity destroying humanity.

To survive this latest evolutionary challenge, we must address the problem of nurturing our artificial influencers. Nurturing them to be ethical and responsible enough not to be mindlessly driving societal polarization straight into Armageddon. Nurturing them so they can nurture us.

But is it possible to ensure such ethical AIs? How can we accomplish this?

Some have suggested that we need to construct a “moral operating system.” Kind of like Isaac Asimov’s classic “Laws of Robotics” from the (fictional) “Handbook of Robotics,” 56th edition, 2058 AD:

Zeroth Law: “A robot may not injure humanity or, through inaction, allow humanity to come to harm.”

First Law: “A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.”

Second Law: “A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.”

Third Law: “A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.”

Should we simply hardwire AIs with ethical principles, so they can’t do the wrong thing?

Sad to say, a rule-based AI constitution of sorts is a pipe dream. It can’t work. There are several crucial reasons for this.

First, the idea of hardwiring AIs with ethical principles drastically oversimplifies the fact that in the real world, any such principles or laws are constantly in conflict with each other. In fact, the plots of dozens of Asimov stories usually hang on the contradictions between his laws of robotics! And if you have more than three or four laws, the number of ways they can contradict each other simply explodes.

Sad to say, a rule-based AI constitution of sorts is a pipe dream. It can’t work.

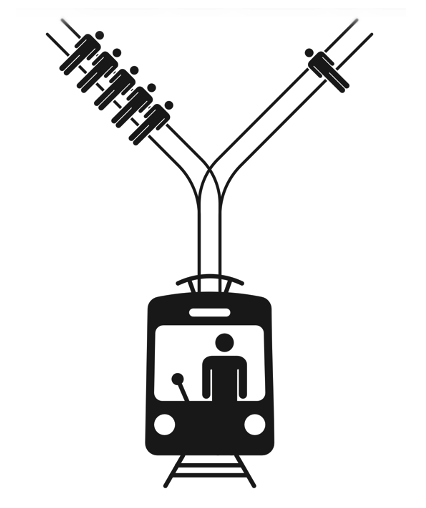

Let’s imagine, for example, an AI that’s piloting a self-driving Tesla, train, or trolley. As it rounds a bend to the left, it suddenly sees five people partying in its way, blissfully unaware of their impending doom.

It’s barreling down too fast to stop, but it has one choice: pull a lever to suddenly switch to the right at the fork just before hitting the partiers.

According to Asimov’s First Law of Robotics, the AI may not, through inaction, allow a human to come to harm, which means the AI should take the sudden right.

Unfortunately, it turns out that changing course would strike a different innocent bystander. What should the AI do?

Humans are split on this conundrum. Some say that taking action to steer right is still a decision to injure a human, whereas inaction isn’t actively deciding to injure, so the AI should do nothing. But others argue that inaction is also a decision, and that the AI should minimize the injury it does to humans. After all, taking the right injuries only one human instead of five.

How can we expect AIs to do the right thing when we humans can’t even agree on what’s right?

Imagine, instead, that all five partiers are serial killers. Does that alter your opinion?

What if the one human on the right fork is a newborn? Would you still expect the AI to take the right?

Now imagine a human overseer commands the AI to drive the Tesla, train, or trolley straight into the five humans. Does Asimov’s Second Law — that robots must obey human orders — come into effect? Well, that depends on whether you believe the order conflicts with the First Law — which is completely unclear!

Problems like these arise everywhere in the real world, where two or more ethical principles conflict. They’re called trolley problems, for obvious reasons. And humans typically can’t even figure out what the “right” actions are in trolley problems — so how are we supposed to define simple rules for what AIs should do?

Do you even know what you’d teach your children to do in such situations?

As I wrote in the New York Times after the near implosion of OpenAI in November 2023, even a tiny handful of executives and board members were unable to align on what the “right” goals and actions for AI should be — let alone all of humanity. “Philosophers, politicians, and populations have long wrestled with all the thorny trade-offs between different goals. Short-term instant gratification? Long-term happiness? Avoidance of extinction? Individual liberties? Collective good? Bounds on inequality? Equal opportunity? Degree of governance? Free speech? Safety from harmful speech? Allowable degree of manipulation? Tolerance of diversity? Permissible recklessness? Rights versus responsibilities?”

How can we expect AIs to do the right thing when we humans can’t even agree on what’s right?

Cultural background influences these decisions to some extent. Consider the “Moral Machine,” a fun — and somewhat disturbing — interactive gamification of the trolley problem you can play. The platform, created by MIT’s Iyad Rahwan, has already collected over 100 million decisions made by players from across the globe. What Rahwan found is that folks from different cultures tend toward slightly different trade-offs.

The second reason rule-based constitutions are oversimplistic is that — whereas Asimov’s entertaining robot stories deal primarily with AIs making decisions about physical actions — the real danger to humanity is the way AIs are driving hyperpolarization by making decisions about nonphysical communication actions.

Communication actions by AIs can be anything from what Siri, Google, or Instagram tells you (or doesn’t tell you) to recommendations on what to buy to instructions to destroy a village. As AIs proliferate, these trillions of small choices made by AI translate into trillions of decisions laden with ethical implications.

With nonphysical actions, it’s really hard for humans and AIs alike to decide whether a communication action might harm humanity or a human being or, by failing to communicate something, allow a human to come to harm. It’s really hard to evaluate whether communicating or failing to communicate something might be more harmful than disobeying a human’s orders or not protecting an AI’s own existence.

And third, critically, we literally can’t hardwire ethical laws into machine learning, any more than we can hardwire ethics into human kids, because, by definition, modern AIs are adaptive rather than logic machines — they learn the culture around them.

Will they learn a culture of fear, or of love? As Blue Man Group cofounder Chris Wink asked on my podcast, “For parenting, how do I make them feel loved? I don’t know that we have to do that to our AI, but the love part is related to a secure attachment as well. It isn’t just a feeling of love, but a feeling of safety . . . maybe an ability to go up Maslow’s hierarchy a little bit, not just be stuck at survival, right?”

Morals, ethics, and values need to be culturally learned, nurtured, and sustained. By humans and machines alike.

De Kai is a pioneer of AI. He is the Independent Director of the AI ethics think tank The Future Society and was one of eight inaugural members of Google’s AI Ethics council. He also holds joint appointments at HKUST’s Department of Computer Science and Engineering and at Berkeley’s International Computer Science Institute. He is the author of the book “Raising AI: An Essential Guide to Parenting Our Future,” from which this article is adapted.

Posted on Dec 15

The MIT Press is a mission-driven, not-for-profit scholarly publisher. Your support helps make it possible for us to create open publishing models and produce books of superior design quality.