Jealousy

What Envy Is: Admiration in Despair

Envy is the basic emotion of social comparison. Here’s how it affects us.

Updated April 24, 2025 | Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Envy is a deeply uncomfortable feeling, potentially socially isolating, and not easy to admit.

- Associated with eyesight, the “evil eye” infects or bewitches and is blind to the goodness in others

- Malicious envy engenders ill-will and even schadenfreude, i.e., taking pleasure in another’s misfortune.

- Envy involves a perceived sense of lack, while jealousy involves a perceived sense of loss.

The Seven Vices: Envy (Invidia) by Giotto, circa 1305-6. Scrovegni Chapel in Padua Italy.

Source: Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain.

As he travels with Virgil from the Inferno into Purgatory in The Divine Comedy, Dante meets those who did not actually commit crimes, but who were guilty of one of the seven capital vices that “lead to sinful acts.” Among them, he finds a group of shades looking more like beggars, huddled closely together and supporting each other, “as they never did in life” (Purgatorio, Canto XIII).

These shades wear clothing made of coarse, stiff goat hair that is “intolerably itchy and rubbed the flesh open,” according to notes by Dante’s translator Ciardi. Most significantly, though, they are all blind because their eyelids have been pierced and sewn together with iron wires. “Through their ghastly stitches, tears forced their way and flowed down from their faces” (Canto XIII). That their eyes are “cruelly mutilated” reflects their “willful blindness” to the goodness in others (Kirkpatrick, 1981).

Says Virgil, “When I saw the penance imposed upon these praying people, my eyes milked a great anguish from my soul.” These are the people who committed the vice of envy, and they will stay in Purgatory until they “feel purged of any taint” of their vice (Canto XIII).

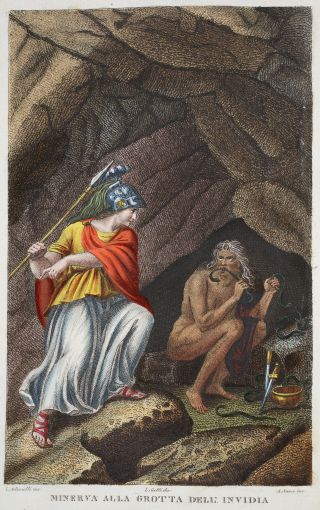

Even earlier than Dante, Ovid wrote vividly of the house where the goddess Envy lives when Minerva comes to give her orders: it is “a black abode, ill-kept, stained with dark gore, a hidden home in a dark valley with no sunshine.” Envy sits inside eating the flesh of snakes, “the proper food to nourish her venom. She is pale, skinny, mean, with teeth red with rust.” Scattered on the floor are half-eaten snakes. “Envy never laughs except when watching pain” (Book II, Metamorphoses).

Minerva visits the goddess Envy, here seen eating poisonous snakes and living in filth, by Luigi Ademollo, 1832. Private Collection. Illustration from Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

Source: Bridgeman Images. Provided by Afro. Used with permission.

Envy is among one of the most powerful emotional forces (Lange et al, 2018). It is an unpleasant, often painful sensation that may include feelings of inferiority and resentment, all produced by the recognition that another person or group has something desired or an awareness of another’s superior qualities (Irish, 2025). Commonly experienced, “deeply uncomfortable” and potentially “socially isolating,” it may also involve a “constellation of emotions,” including anger, anxiety, hostility, and disappointment (Redelmeier et al., 2023). It is “admiration in despair” (Poor Richard Jr’s Almanack, 1906).

As in Dante, envy has a long anthropological history of association with eyesight and particularly, the evil eye: the envious person casts a malicious gaze on a rival. The envious eye is a diseased eye that has the power to infect or even bewitch—even the root of invidious involves seeing and not seeing (Irish, 2021).

Essentially, envy is the “emotion of uneven social comparison,” writes Dr. Bradley J. Irish, Associate Professor of English, in his new scholarly book, The Rivalrous Renaissance (2025). “There is literally no Shakespearean drama that could not be somehow considered in terms of envy, including notions of malice and spite,” and Irish emphasizes, as well, the importance of Ovid’s dramatic characterization in taking hold of our imagination (2021).

The evil eye of envy is pervasive in many cultures.

Source: Wikimedia Commons/Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

In more recent years, social media, used by more than 4 billion people worldwide, may even engender overt envy and decrease well-being by providing a “fertile ground” for destructive social comparison (Meier and Johnson, 2022). Though studies are often cross-sectional, there seems to be a relationship involving social media, depression, and envy, including the notion of Facebook depression (Carraturo et al., 2023).

THE BASICS

Envy is considered shameful, and no one likes to admit it (Irish, 2021). It is often seen as a “covert, hidden vice” (Dickie, 1975) that people try to conceal because it tends to elicit public disapproval (Parrott and Smith, 1993).

Though envy seems universal, in most cultures, it is considered a sin since it violates social conventions that encourage “supportive rather than competitive, begrudging reactions to another’s success” (Smith and Kim, 2007). In other words, it is a “social disease that corrupts” our relationship with our neighbors (Irish, 2021).

Detail from “The Table of Mortal Sins (Invidia, Envy),” by Hieronymus Bosch, 1480. Prado Museum, Madrid.

Source: Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain.

Some researchers, though, suggest there are at least two kinds of envy—benign envy and malicious or malignant envy (Smith and Kim; Irish, 2025; van de Ven et al., 2015; Lange et al.; Battle and Diab, 2024; Dai et al., 2024). Both derive from the same sense of social comparison, but benign envy entails a motivation to improve oneself and emulate the envied person, while malicious envy involves resentment and hostility and an actual wish to do someone harm (Lange et al). The ancient Greek poet Hesiod was the first person to differentiate praiseworthy (benign) envy from blameworthy (malicious) envy (Irish, 2021).

Malicious envy may lead to schadenfreude, i.e., the experiencing of pleasure at another’s suffering (Irish, 2025). Schadenfreude is also seen as socially undesirable, but it has become a part of our culture, most notably in television entertainment that fosters laughter at the expense of someone’s public humiliation (Suter and Dőveling, 2024.) “We live in a society of spectacle,” writes Susan Sontag, where “compassion is an unstable emotion” (2003).

Envy, from “Virtues and Vices,” by Netherlandish artist Zacharias Dolendo, 1596-97. Metropolitan Museum of Art. NYC

Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art/Public Domain. Credit: The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1949.

The Bible cautions against taking pleasure in the suffering of another, “Do not rejoice when your enemy falls, and let not your heart be glad when he stumbles” (Proverbs 24:17). Schadenfreude is particularly likely to occur if the misfortune seems deserved (Cikara and Fiske, 2013), as, for example, when public figures are caught in crimes, exposed, and receive their comeuppance.

In general, schadenfreude is a passive, muted pleasure, but when a person has some responsibility for the adversity of another, it may evolve into gloating (Karasu, 2016). When a victim is seen as not having responsibility for his fate, he is more likely to receive our sympathy (Karasu).

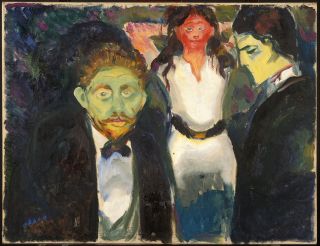

What about jealousy? Envy and jealousy are “affective siblings,” i.e., connected but distinct: While envy involves a perceived sense of lack, jealousy involves a perceived sense of loss. There is a “visceral quality,” or “felt quality,” and sometimes even a “thermal quality” to jealousy, with its “cold blasts” or “flames,” writes Irish (2025).

Jealousy is sometimes thought of as a three-person emotion, with its sense of possessiveness, and occurs in the context of relationships (Parrott and Smith; Smith and Kim). It tends to produce justified anger, whereas envy more likely produces “unsanctioned ill will” (Parrott and Smith). And while envy is a disease of the eyes, jealousy can also create the “green-eyed monster,” as Shakespeare wrote in Othello (Act III, Scene 3, 170).

“Jealousy,” by Norwegian artist Edvard Munch, 1907. Munch Museum, Oslo.

Source: Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain.

Jealousy and envy may co-occur, particularly when a jealous person can envy a rival as well as fear a loved one’s loss. Increasingly, though, jealousy and envy are “confounded,” not only by laypeople but also by scholars, to the detriment of research on both concepts (Parrott and Smith).

References

Battle L; Diab DL (2024). Is envy always bad? An examination of benign and malicious envy in the workplace. Psychological Reports 127(6): 2812-2832.

Carraturo F et al (2023). Envy, social comparison, and depression on social networking sites: a systematic review. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 13: 364-376.

Cikara M; Fiske ST. (2013). Their pain, our pleasure: stereotype content and schadenfreude. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1299: 52-59.