April 15, 2024

5 min read

New Digital Cognitive Tests Spot Dementia Warning Signs

As the first effective Alzheimer’s drugs are adopted, companies are racing to bring accurate screening tests to market

Adam Piore

This article was produced in partnership with the Davos Alzheimer’s Collaborative by Scientific American Custom Media, a division separate from the magazine’s board of editors.

Any primary care doctors have had a complicated relationship with tests designed to screen their patients for Alzheimer’s disease. Beyond recommending a few lifestyle changes—tweaks to diet, exercise and sleep most would recommend anyway—there was little they could do to help patients with a confirmed diagnosis.

As new drugs expand the options for treating and preventing Alzheimer’s, demand from older people worried about their mental fitness and seeking routine screening for Alzheimer’s and other dementia is expected to rise quickly. In anticipation, several commercial firms are racing to bring to market new digital screening tools that can detect warning signs that the disease could be developing. (Diagnostic tools, by contrast, are used to establish the presence of the disease, usually by detecting amyloid.) Many of these new screening tools use artificial-intelligence algorithms and can be administered by medical assistants without extensive training. They hold out the promise of inexpensive and noninvasive methods of screening people for Alzheimer’s.

“Dementia is the number-one fear of people over 55,” says David Bates, CEO of Boston-based Linus Health, a digital assessment company. “You have drug companies that are about to be advertising their drugs. And you’re going to have commercials and marketing stoking that fear to drive people to ask for the drug. So you’re going to have this onslaught of demand in the health system. Primary care doctors will not be able to meet that demand. They’re going to get overwhelmed.”

PET imaging and tests of cerebrospinal fluid, which document the presence of amyloid beta plaques in the brain, are currently the gold standard for providing a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s. But these tests are too expensive and cumbersome to administer to meet the anticipated need for Alzheimer’s screening in large populations. Although blood tests that can flag the buildup of amyloid are beginning to emerge from the lab, they are not yet widely available.

For years, primary care physicians have instead relied on pen-and-paper cognitive tests to screen patients with mild cognitive impairment, but these tests can take 20 to 30 minutes to complete and require a trained administrator. The “reality is primary care doctors don’t have that time,” says Brad O’Connor, CEO of CogState in Australia.

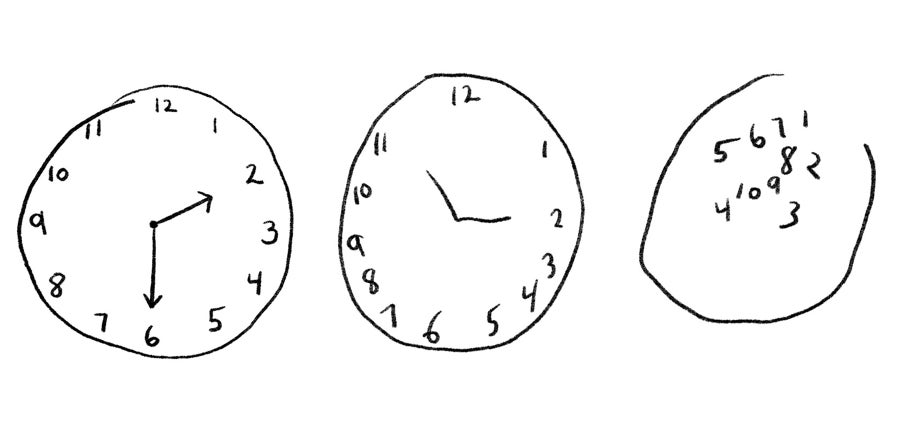

A test sold by Linus Health combines an established pen-and-paper test based on a simple drawing test with added artificial intelligence to make it easier to administer and more powerfully analytic. In the test, a patient is asked to draw a clock with the clock hands indicating a specific time. The task engages disparate areas of the brain involved in motor, visual, analytical and other functions that are often impaired by dementia.

In the original version of the test, the patient draws the clock on a piece of paper, and a trained observer evaluates the results and refers the patient on for further testing. Linus’s version, originally developed at MIT and commercialized by a company called Digital Cognition Technologies that Linus later acquired, has the patient draw the clock using a stylus on the iPad while an AI algorithm tracks the movement of the hands, measuring a wide array of variables, including the time it takes to respond to instructions, the size and characteristics of the drawing itself, and the way the patient moves their hands. The AI algorithm was trained on thousands of patients with dementia of varying severity, as well as healthy people. The data were gathered from local clinics and longitudinal epidemiological studies, including both the Framingham Heart Study and a Rush Hospital study documenting the health of primarily minority populations.

In a study, scientists from Linus and Harvard Medical School found that they could detect signs of cognitive dysfunction in less than three minutes in patients who didn’t previously report impairment. The scientists checked each detection with PET scans, which can reliably identify buildup of amyloid plaque in the brain, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s. The paper was published in Neurology in 2021.

Read More from This Report

The New Age of Alzheimer’s

The assessment is simple enough to do in a primary care practice during an annual wellness visit, administered by a medical assistant with minimal training. The company has raised $64 million since its founding in 2019 and completed early testing of the product in 2023. The product is now being rolled out in the Indiana University Health System, at UMass Medical School, at Emory University and in about 50 small medical practices. It has so far been used on several thousand patients.

“We are not suggesting that this is the only cognitive assessment you should ever do, but it’s a really low-cost, noninvasive, easy assessment that will identify those first changes and get people at least on the pathway for assessment of the issues—and also conversely conclude this person is not at risk to decline in the next five years. Which really helps doctors with the ‘worried well,’ because they’re fine, but they take up a lot of healthcare resources.”

Several other firms are working on digital tests aimed at addressing this growing demand.

CogState plans to roll out Cognigram, in the U.S. early next year. It uses a virtual deck of playing cards, which can be displayed on a computer screen, to assess memory and cognition. The company has partnered with the Japanese drug maker Eisai, the makers of Leqembi, to get it into the hands of doctors.

CogState is perhaps best known for computer-based cognitive assessments designed to measure changes in cognitive function over time. Its Cogstate Brief Battery test, which is widely used in clinical trials, healthcare and academic institutions, uses the digital cards to establish a baseline in areas such as attention, visual learning, and working memory and then tracks changes over time through follow-up assessments. Cognigram, however, does not require a baseline digital assessment for its screening, which allows doctors to identify patients for further tests, says O’Connor. Instead, on its first use, the patient score is compared to an age-matched normative dataset. In subsequent tests, patient scores are compared to both the normative dataset and previous patient scores.

The test, which can be administered by a medical assistant in a doctor’s office or even done remotely from home, performed well in several studies, including one published last year in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease in December. It compared the performance of 4,871 cognitively unimpaired adults to that of 184 adults who met clinical criteria for mild cognitive impairment.

“It all sounds very simple,” says O’Connor, “but these tests have been proven to be really sensitive to the earlier stages associated with disease.”

Cognivue, based in Victor, New York, recently released a digital cognitive testing technology that first screens for potentially confounding factors like visual and motor impairments, then adjusts the test to account for these impediments, which otherwise can muddy the results. It does so by displaying a bunch of white dots on a black screen contained in a green, wedge-shaped outline. As the dots move in clockwise and counterclockwise directions, the patient is instructed to keep the dots within the green wedge by turning a knob that controls the position of the wedge.

To measure cognitive impairment, the Cognivue program asks patients to distinguish real words displayed on the screen from nonwords or to distinguish letters from random symbols. Other tests ask the test subject to distinguish between different shapes. The test increases in difficulty until the subject reaches the limits of their abilities, and uses AI algorithms to compare the subject’s performance to people with similar age, education levels and other demographic factors, evalutating performance in visual acuity, memory, executive function and other areas.

This article is part of The New Age of Alzheimer’s, a special report on the advances fueling hope for ending this devastating disease.

Learn more here about the innovation ecosystem that Davos Alzheimer’s Collaborative is building to speed breakthroughs and end Alzheimer’s disease. Explore the transforming landscape of Alzheimer’s in this special report.

Adam Piore is a freelance journalist based in New York.