Five ways AI could improve the world: ‘We can cure all diseases, stabilise our climate, halt poverty’

It is not yet clear how the power and possibilities of AI will play out. Here are the best-case scenarios for how it might help us develop new drugs, give up dull jobs and live long, healthy lives

- Coming on Friday: Five ways AI might destroy the world

Interviews by Steve Rose

Thu 6 Jul 2023 05.00 BST

Recent advances such as Open AI’s GPT-4 chatbot have awakened the world to how sophisticated artificial intelligence has become and how rapidly the field is advancing. Could this powerful new technology help save the world? We asked five leading AI researchers to lay out their best-case scenarios.

‘More intelligence will lead to better everything’

In 1999, I predicted that computers would pass the Turing test [and be indistinguishable from human beings] by 2029. Stanford university found that alarming, and organised an international conference – experts came from all over the world. They mostly agreed that it would happen, but not in 30 years – in 100 years. This poll has been taken every year since 1999. My guess has remained 2029, and the consensus view of AI experts is now also 2029.

Everything’s going to improve. We will be able to cure cancer and heart disease, and so on, using simulated biology – and extend our lives. The average life expectancy was 30 in 1800; it was 48 in 1900; it’s now pushing 80. I predict that we’ll reach “longevity escape velocity” by 2029. Now, as you go forward a year, you’re using up a year of your longevity, but you’re actually getting back about three or four months from scientific progress. So, actually, you haven’t lost a year; you’ve lost eight or nine months. By 2029, you’ll get back that entire year from scientific progress. As we go past 2029, you’ll actually get back more than a year.

Most movies about AI have an “us versus them” mentality, but that’s really not the case. This is not an alien invasion of intelligent machines; it’s the result of our own efforts to make our infrastructure and our way of life more intelligent. It’s part of human endeavour. We merge with our machines. Ultimately, they will extend who we are. Our mobile phone, for example, makes us more intelligent and able to communicate with each other. It’s really part of us already. It might not be literally connected to you, but nobody leaves home without one. It’s like half your brain.

If the wrong people take control of AI, that could be bad for the rest of us, so we really need to keep pace with that, which we are doing. But we already have things that have nothing to do with AI, such as atomic weapons, that could destroy everyone. So it’s not really making life more dangerous. And, it can actually give us some tools to prevent people from harming us.

The rate of change will be difficult for some people. The railways changed the US, but it took decades; this is changing it in months. If we were in 1900 and I went through all the different ways people made money, and I said: ‘All of these will be obsolete in 100 years,’ people would go: ‘Oh, my God! There’s gonna be no jobs.’ But in fact, we have more jobs today – in areas that were really only invented in the last few decades. That will continue.

We’ve made great progress but there are still people who are desperate. More intelligence will lead to better everything. We will have the possibility of everybody having a very good life.

Ray Kurzweil, computer scientist, inventor, author and futurist

‘We can use AI tools right now to help fight climate change’

Everyone wants a silver bullet to solve climate change; unfortunately there isn’t one. But there are lots of ways AI can help fight climate change. While there is no single big thing that AI will do, there are many medium-sized things.

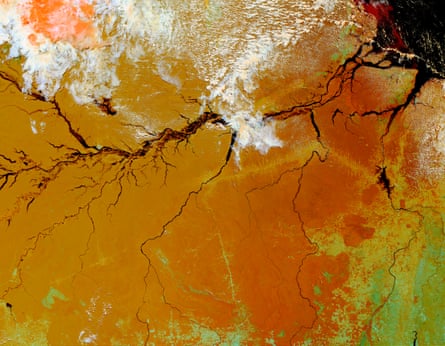

The first role AI can play in climate action is distilling raw data into useful information – taking big datasets, which would take too much time for a human to process, and pulling information out in real time to guide policy or private-sector action. For example, taking satellite imagery and picking out where deforestation is happening, how biodiversity is changing, where coastal communities are at risk from flooding. These kinds of tools are already starting to be used by organisations around the world, from the UN to insurance companies, and we’re working to scale them up and improve them.

The second role is optimisation of complicated systems – such as the heating and cooling system in a building, where there are many controls that an algorithm can operate efficiently. Smart thermostats have become mainstream in our homes, and now we’re starting to see that for skyscrapers and factories. Many companies are improving energy efficiency, and there is a lot of progress still to be made, especially in industries such as steel and cement, which are often resistant to adopting new technologies.

The next theme is forecasting. AI can’t predict something big-picture like what’s going to happen to the economy – but forecasts make sense for narrow problems with lots of data, such as what the power demand is going to be at a particular time, or what power is going to be available based on the sun and the wind, forecasting how a storm is going to move, or the productivity of crops based upon the weather.

Thinking of AI as a futuristic tool that will lead to immeasurable good or harm is a distraction from the ways we are using it now

The fourth theme is in speeding up scientific simulations, such as in climate and weather modelling. We have really good climate models, but sometimes they can take months to run, even on supercomputers, and that is an obstacle. We understand climate change very well but that doesn’t mean we know exactly what is going to happen at each point. So, having faster climate models can aid local and regional responses.

AI in climate action isn’t about what computers can do in the far future – we can’t trust some speculative future technology to rescue us. Climate change is already killing people, and many more people are going to die even in a best-case scenario, but we get to decide now just how bad it gets. Action taken decades from now is much less valuable than action taken soon. Thinking of AI as a futuristic tool that will lead to immeasurable good or harm is a distraction from the ways we can and are using AI tools right now, and what we can do to align them with what’s best for society.

David Rolnick, assistant professor and Canada CIFAR AI Chair, McGill University School of Computer Science, Montreal